This interview was conducted in 2008 by Meilys Cruz Fernandez, then a student and now professor, head of the Faculty of Humanities' Department of Journalism at the University of Camagüey. It was published on the website IPVCE.ORG directed by Daian Gan. Both Meilys and Daian are Camaguey Vocational School graduates.

by Meilys Cruz Fernández.

The National Educational Building Group assigned him the task of developing the project for the second of the big vocational schools, the one to be built in Camagüey.

Reinaldo Togores Fernandez was working then in the preliminary design for the Armed Forces Higher Officers Academy to be built in Bacuranao. Faced with the dilemma of deciding to which of the two giant projects would he dedicate his effort, he didn't hesitate in his choice: the 'Maximo Gomez Baez' School City.

Did you think you would sometime be an architect?

School buildings of the time were built using the "Girón" prefabricated system, with long horizontal blocks, all of the same height, side by side as in military formation. That monotony became even more evident in the design of the façades: always windows to the north in uninterrupted bands; to the south the same, but now windowless, the aisles were to be on that side. And at the ends, blind concrete panels. Achieving a building complex free the hitherto prevailing rigidity constituted a real challenge for a skilled specialist. However, both experience and creative spirit prevailed.Evaluating the outcome, Fidel Castro said:

The National Educational Building Group assigned him the task of developing the project for the second of the big vocational schools, the one to be built in Camagüey.

Reinaldo Togores Fernandez was working then in the preliminary design for the Armed Forces Higher Officers Academy to be built in Bacuranao. Faced with the dilemma of deciding to which of the two giant projects would he dedicate his effort, he didn't hesitate in his choice: the 'Maximo Gomez Baez' School City.

Destiny: Camagüey

I was born in Havana in 1939, on June 6. I studied high school with the Jesuits at the Colegio de Belén. Yes, where Fidel. My first destination as an architect was Camagüey, in the rural housing plan undertook in 1966 by the Vice-Ministry Housing.

Did you think you would sometime be an architect?

I had always been interested in painting and movies. Architecture was a late discovery but which summarizes basic elements of those, my earliest interests.With what professional and personal expectations did you assume the task of building our school?

I went to work at the National Educational Building Group, under the direction of Josefina Rebellón in 1972. I then had the experience of working in housing and urbanistic projects in Camaguey and Santiago de Cuba from 1965 to 68, and later in the Ministry of Light Industry's development department

addressing issues related to the furniture industry, with particular attention devoted to what concerns design.

At the same time, since 1970, I taught design at the Havana School of Architecture (ISPJAE). At the NEBG I found myself with a maelstrom of work to which responding was difficult. Given my previous experience, on arriving I was entrusted with the general planning of the Armed Forces Higher Officers Academy, to be built in Bacuranao. Already submitted the preliminary draft, the need arose to prepare the designs for the second of the major vocational schools, that of Camagüey, responding to the intention of providing a center of these characteristics at each provincial capital.

I then saw myself with two giant projects in my hands, and faced with the dilemma of choosing to which one them I would devote my direct effort. On the one hand, the Military Academy offered a better chance of, so to speak, "social promotion", although at the price of less freedom in imposing my ideas regarding design. This becomes evident if we compare what was actually built with the distribution shown in my initial project.

I did not hesitate in my choice. The overall project of the Academy was handed over to the Architect Eva Aguilar, my participation being limited to the administration's building and in particular to the Officers Club, one of the works with which I've been more pleased but of which I have no photos because of the limitations inherent the fact of it being a military installation.

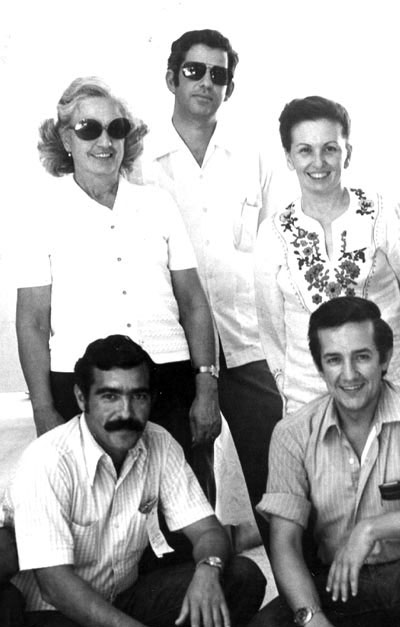

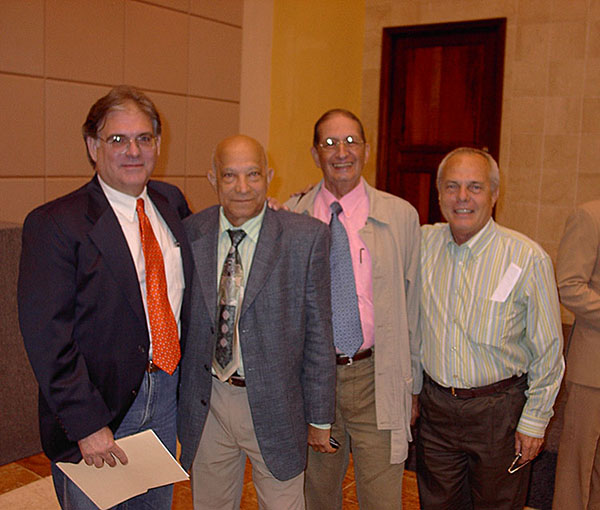

A project the size of the Maximo Gomez Vocational School job is never a single person's job. I was fortunate in counting with an exceptional team. I counted with Carlos López Quintanilla, who had been my brightest student in the Havana Faculty of Architecture (ISPJAE) as assistant designer and Heriberto Duverger, author of the "Volodia" school at Lenin Park as a consultant (Figure 2). Taking care of the technological aspects, Luis Blanco and Williams Calderón in structural calculus, Julia Delgado (Figure 1) in roadway projects and earthworks, Humberto Zarraluqui in electricity, Tony Lopez Cruells with the hydrosanitary systems and Luis Rubio in landscaping.

Figure 1. Standing, to the left engineer Julia Delgado, roadays and earthworks designer and to the right Josefina Rebellón, head of the National School Building Group. Holguin, 1980.

Figure 2. In the picture, taken in the Dominican Republic during the presentation of the Santo Domingo Architectural Guide, from left to right, Gustavo Moré, director of the AAA magazine in Santo Domingo, Heriberto Duverger, editor of the Guide, followed by Roberto Segre, Latin American Architecture historian and critic and finally, to the right, Carlos López Quintanilla, project partner at the Vocational School.

Hands On!

School buildings of the time were built using the "Girón" prefabricated system, with long horizontal blocks, all of the same height, side by side as in military formation. That monotony became even more evident in the design of the façades: always windows to the north in uninterrupted bands; to the south the same, but now windowless, the aisles were to be on that side. And at the ends, blind concrete panels. Achieving a building complex free the hitherto prevailing rigidity constituted a real challenge for a skilled specialist. However, both experience and creative spirit prevailed.

Breaking preconceived stereotypes is not easy, but local authorities at that time enthusiastically supported my ideas. There is a specific person without whose support this school would not have been what it is: Robertico Valdés, then head of the Construction Ministry (MICONS) in the province. (Figure 3).

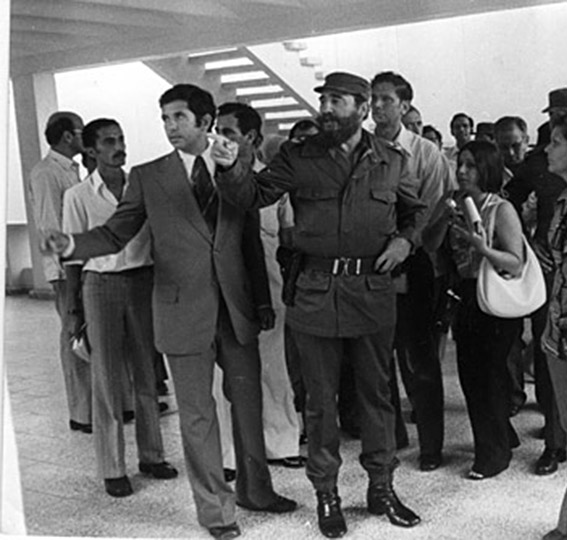

Figure 3. Taken during Fidel Castro's tour of the school on the day of its inauguration. Behind Fidel, Robertico Valdés, head of the Construction Ministry in the province (Photo: National Information Agency).

From an architectural point of view, was the "school city" concept something new for you back then?

The significance of education in the formation of a "new man" to the measure of their ideals has been a constant in the thinking of social reformers since the seventeenth century. And life and work in common was postulated as the most effective way to achieve the desired goal. The "phalanstery" proposed by Fourier would ideally accommodate 1620 people. About two thirds of our school. So the idea is truly not so new. Although in the case of utopias materializing them is somewhat more difficult than describing them.

Which distinctive elements did you take into account for the building's design? (When I speak of "distinctive features" I mean those aspects related to architecture, not strictly technical, which determine the singularity of a building).

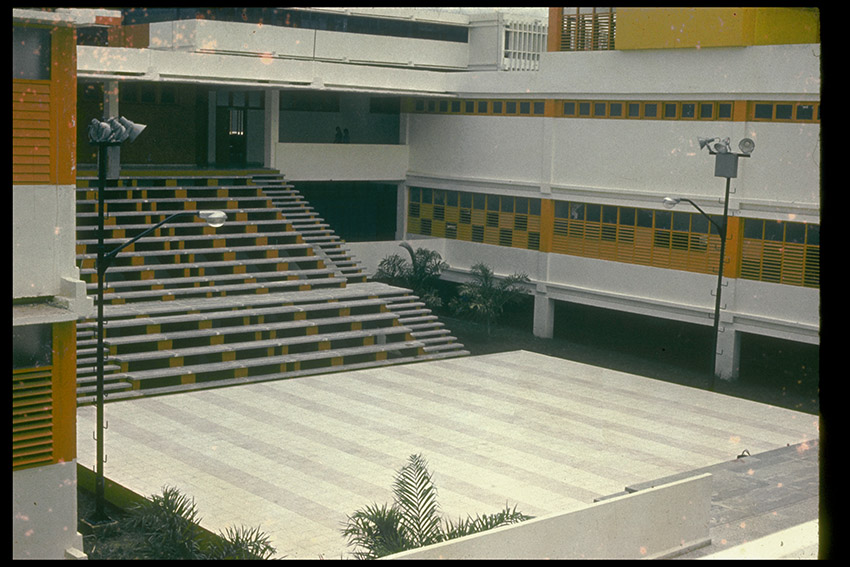

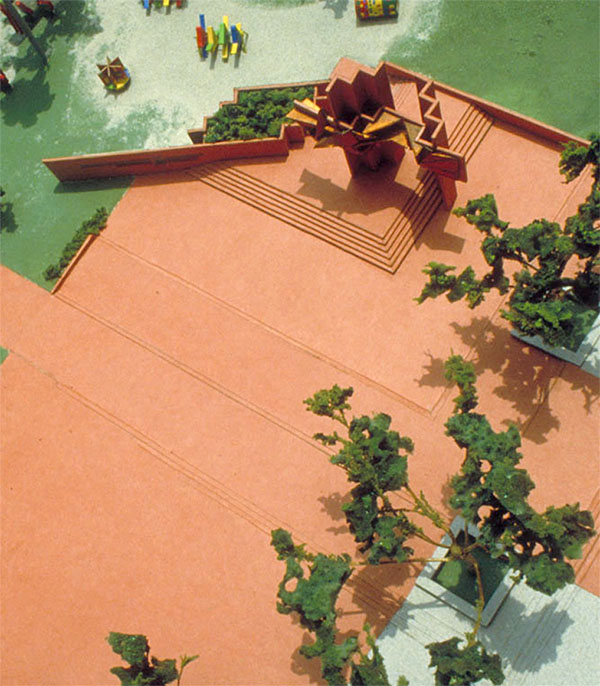

As a Basic Design professor at the School of Architecture I had spent a long time studying issues related to the influence that shape, color, volumes and spaces have in the way that architecture is perceived by the user. What I tried, from the point of view of design, was to break with the horizontality, the parallel alignment of buildings, the blind building endings and the lack of visual connection to the terrain. The east-west alignment of classroom blocks and bedrooms was conditioned largely by climatological conditions, particularly sunlight. However, the common use premises such as library, museum, computer center, theater, etc., are grouped in a north-south orientated central block acting as a symmetry axis around which the whole is articulated. If the depth of class and bedroom blocks is preset to meet standard distributions, mounting flexibility with cranes on wheels is used to achieve far more complex spaces in the other buildings. Some things were inherent to the construction system and could not be changed. For example the limitation on height, no more than four stories. The personality of this school lies largely on having achieved to visually overcome this limitation. For this purpose two staggered plan towers that house rooms intended for laboratories were placed at the ends of the classroom blocks bordering the central block. To emphasize these towers we added projecting volumes (used for storage) that were painted bright yellow color. A sudden change in height takes place beside these towers, to the library's two stories (the lower one resting directly on the ground), thus emphasizing by contrast the impression of height. Viewed from the main entrance a perspective effect takes place due to which the buildings -the dormitories- farthest away in the background look smaller, then the approaching classroom buildings and lastly, closer by, the laboratory towers on either side of the central block, lower in height as I said before and linked to the ground by the colonnade on which the library is supported (Figure 4).

Figura 4. Perspectiva del proyecto mostrando el esquema original de colores (1976).

Another aspect in which we resort to a kind of optical illusion is in solving the dormitories' blind endings. At the ends of the classroom blocks I had placed the main staircases, thereby justifying these opening them with terraces. But I could not do this in the dormitories since these were typical projects, drawn up by architect Andrés Garrudo (designer of the "Lenin" Vocational School). The solution was to paint these façades so that the play of light and dark colors suggesting effects of light and shadow as well as the use of warm colors (that "advance" visually) and cool colors (which "recede") would give the impression of the relief that these walls lack (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Graphics on the dormitories endings. (Photo by Roberto Segre, 1976)

As for the relationship with the terrain, there were previous experiences -for example in child care centers - with the use of long columns capable of supporting the first floor's structural level directly on the ground, dispensing with the use of pedestals and of the "0.0 structural level". We took advantage of this resource mainly in the interconnecting galleries, in which it also accounted for an economy of resources by removing an entire level of beams and slabs, allowing students to walk directly on a landscaped terrain (Figure 6).

Figure 6. A gallery which rests directly on the ground. The design of railings and brise-soleils constructed from interlocking panels can be seen.

One detail that should be mentioned is the design of railings and brise-soleils that plays with the very nature of the system: a montage of panels, thus contributing to the formal coherence of the whole.

On joys and remembrances.

Evaluating the outcome, Fidel Castro said:

“(…) this school can be described as wonderful. It must be seen. They had told me about it, we visited several times when it was under construction, but I could not even imagine how it would be when it was finished. And now we see it completely finished; they may be some little details missing, some railings on certain stairs, but things already insignificant. From the point of view of its material base , considering the project, built according to the Giron system, but with a specific conception for this school, considering the concentration and distribution of its facilities, considering its architecture, at this moment it is undoubtedly the best in Cuba.(…) In fact, this school speaks very highly, but very highly, of the Camagueyan builders, …and will remain here as a symbol of the creations that can be achieved by man's sweat, by human labor. I am sure that they will always feel satisfied to see the work they have concluded with their effort and dedication.”

Do you remember any particular detail of those days working in the School City's construction?

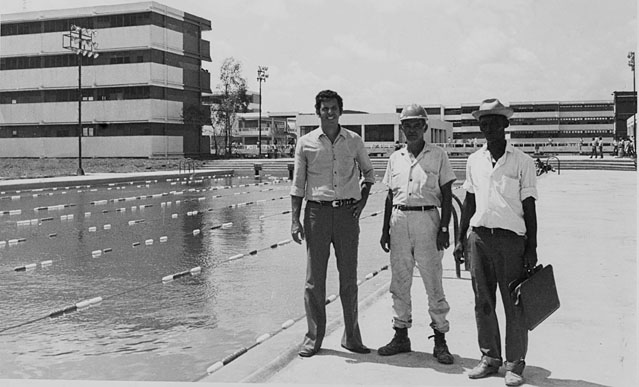

The dedication of everyone, the faith demonstrated in the value of what they were doing. I remember that meeting the goal set for finishing the construction demanded continuous revisions of the project. A project which my chiefs considered already finished. Not wanting to leave those revisions to other people, I opted for using my pending vacations and marching to Camagüey. There I spent the whole month of August working -then truly a "volunteer"- at the construction site. (Figure 7).

Figura 7. The architect, on the left with the hydrosanitary installers chief and the head of the prefab assembly brigade.

From the inauguration day I remember the tour next to the then head of government, Fidel Castro and of his interest in all of the project's details. I would like to share with you a photo I've kept since then (Figure 8). It was taken by Fernando Lezcano, from the Granma newspaper, who sent it to me through our mutual friend the great photographer Osvaldo Salas.

The place where it was taken will be quickly identified by all of you: the gallery between the theater and the cultural block's small amphitheater. At that point Fidel was asking me about the missing railings at either end of the amphitheater, which had not been installed yet (Figure 9). To this he referred later in his inaugural speech as one of the school's pending details. Some of Fidel's considerations in the school's inaugural address certainly arose from our conversation that day:´In this school the constructive experience gained is reflected, an experience that has been gathered over these years of an intense school construction program. It even has a finished amphitheater, which I think they will inaugurate tonight. I understand that they will be presenting there a ballet tonight.As we parted he told me that I had not mentioned my name in the speech because did not remember it. Disadvantages of a family name as unusual as mine!

The gymnasium is complete and is magnificent, just as the theater, although the ventilation remains a problem to be solved; everything is ready, but there are some pending equipments, so some movie will have to watched with a bit of heat.

It has a lovely library and an Olympic swimming pool with every detail, a magnificent dining room, even with a small lounge for learning how to eat; a number of special classrooms where nothing is missing -chorus, dance, and so on- for the two levels: secondary and high school.

The school's functional solutions are really good, the distances are short and the disposition of all of the buildings has been made with real artistry. We must congratulate the school buildings group and the architect who designed this school.‘

Figure 8. Moment in the tour by the cultural block's small amphitheater.

Figura 9. Small amphitheater days after the opening, still without handrails.

The author and his work…

Few architects of my generation have had opportunities like this. Unfortunately, most of our work (mine and that of most of the architects of the post-revolutionary promotions) has remained on paper, without ever being built. The important projects, where the architect would have been able to express himself freely have been scarce in the years of our professional lives. And such works were always entrusted to those from an earlier generation, to those who had begun their careers before the revolution.

For my part I have never lost enthusiasm in my work. I have been awarded in several competitions of Design and Architecture, although only one of them, a monument to José Martí in Rome, has come to be translated into a work built. As was the case of the National Competition for Agricultural Cooperatives Housing (1981) which proposed a modular design that enabled the expansion of the built space to suit the changing needs of the family. Or the most recent one (1989), a monument to Lázaro Peña, founder of the Cuban Workers' Confederation (with René sculptors Juan Negrin and Quintanilla), for the construction of which all workers at the time contributed with five cents. (Figure 10).

Figura 10. Model of the monument to Lázaro Peña, Havana, 1989.

How does the architect regard his work today, after so many years?

This work shows that the role of the architect can go beyond the merely technological. That despite using a system of prefabricated elements it is possible to build what my teacher, Ricardo Porro, described as a poetic environment for human activity.

In our midst it has been very difficult to get the role of the architect as a creative artist accepted. In fact, the Cuban Writers and Artists Association (UNEAC) took almost thirty years to admit us (in 1991) a small group of architects as members of the Association of Plastic Artists, and that as a Section which was not called Architecture, but "Environmental Design".

I hope someday this work will contribute to the recognition, among Cubans, of an artistic category in the architecture we have designed in these nearly fifty years.

If you could change something in the construction or the design of the building, what would it be?

I did not succeed in complementing this work, as was my wish, with the work of a number of artists. In the library there is a wall panel on which a mural painting designed Raul Martinez should be placed. Its advanced conception raised fears among local authorities. I made efforts like appealing to influential government figures like Osmany Cienfuegos, who did not object to the work, but still didn't achieve the necessary support for the painting to be carried out. Unfortunately, Raul has passed away. Maybe someone someday will recover that sketch and reproduce it, at last, in the place that was meant for it. Perhaps one of you?

As for the Maximo Gomez statue, I had met Delarra in 1959 when he installed a series of sculptures on Havana University's monumental stairway. I found the expressionist style he then had suitable. There was no official support for his intervention in the school's project, but he undertook it with enthusiasm.

The figure was as big as would fit in the old Centro Habana warehouse he used as a studio. The one that stood for the inauguration of the school was made out of plaster with a patina that made it look like bronze. Only months later, when the plaster model began to crumble due to the weather, we managed to get it cast in bronze.

Some have criticized the quality of this sculpture. Me myself, from what I knew about his previous work, would have expected it to be not so conventional. It would have been better to summon a competition but for this the official support, which we lacked, was necessary.

We did some things when it was only up to us. For example, in the dining hall where Carlos Lopez designed the lamps and Heriberto Duverger the excellent mural graphics. (Figure 11).

Figura 11. Lamps (Carlos Lopez's design) and mural graphics (designed by Heriberto Duverger) in the dining hall.

Today those who write about architecture in our land usually omit, except for rare exceptions1, the schools built during the Seventies and in particular this one, which in its inauguration was described as the best in Cuba. Could it be that perhaps this distinction still causes resentments which motivate this neglect?

But the buildings are there. You, who have experienced it, are the best informed critics. To you the last word belongs.

Other details... for those who want to know.

In 1991 I registered as a freelance creator in my capacity of member of the UNEAC (Environmental Design section of the Association of Plastic Artists).

Since 1982, when I was the keynote speaker at the Advanced Design Methods board during the First Scientific-Technical Conference for Construction, I have been engaged in research on Computer Aided Design and Computer Graphics. Already in my capacity as freelance creator I was offered the opportunity to engage in research related to Graphic Expression in Engineering in the university of Cantabria (Santander, Spain) as well as teaching at its Department of Geographical Engineering and Graphic Expression Techniques (Figure 12).

I've spent the last years doing this, having obtained during that time the degree of PhD in Civil Engineering with a thesis on "Computational Geometry Methods Applied to the Design of Space Structures".

I've been invited as guest professor in Master's Degree classes at the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés (La Paz, Bolivia), the Tomas Frias Autonomous University (Potosi, Bolivia) and the National University of the Northeast (Corrientes, Argentina).

I am co-author of the only book in Spanish on Visual LISP programming for Autocad2, published in 2003 by McGraw-Hill. During this period I have published research papers in Germany, Argentina and Spain.

It has been years since I visited the school. I did it quite often during the first years, when I still worked at the National School Building Group (GNCE) and later at the National School Building Projects Enterprise. Afterwards working in the Ministry of Construction' Projects Direction and later in the Executive Secretariat for Nuclear Affairs, opportunities to visit the school became more scarce. But wishes to do it have never been lacking. So, see you soon! -I hope.

Figura 12. Lecture by the architect at the University of Cantabria (2003).

Small lessons on Architecture:

The parallel arrangement of buildings and the limitation in the building blocks depth was originally justified by the mounting equipment to be used, the Soviet KB-100 tower crane. But I soon discovered that in reality this crane, that moving on rails required preparing a perfectly level embankment was not used on site.

This was especially costly in rough terrain, as besides that the earthwork needed to install the crane was considerable, when the assembly was finished all that work had to be undone. So what was actually used were cranes on tires or caterpillar tracks that were much more flexible in their location.

Another factor contributing to the horizontal appearance of Girón schools was the fact that the buildings were always separated from the ground by a structural level on pedestals, -the then called "0,0 structural level"- which reinforced the impression of horizontal blocks unrelated to the site's topography.

Meilys Cruz, Camagüey, April 28, 2008.