| Photos: R. Togores Archive. | Versión Española. |

As a Basic Design professor at the Havana School of Architecture I had spent a long time studying issues related to the influence that shape, color, volumes and spaces have in the way that architecture is perceived by the user.

Basic Design in the seventies was heir to some experiences that in the past decade counted with an enthusiastic promoter in Joaquin Rallo, and whose untimely death aborted. In its final form it was the product of a team effort maintained for several years and which included the contribution of specialists in diverse subjects (1). This way our teaching was updated following the most recent European developments, such as the Basic Design for Architects course taught in Ulm since 1962 under the guidance of Claude Schnaidt and the research on the psychology of perception applied to architecture by Professor Sven Hesselgren and his Swedish colleagues (2).The course's activity was aimed at making the student discover, in the organization of the visual field, those factors which determine its coherence and which would correspond, according to Kevin Lynch, to:

"physical properties that relate to mental image identity and structure attributes... what might be called 'imageability': that quality in a physical object which gives it a high probability of evoking a strong image in any given observer. It is that shape, color, or arrangement which facilitates the making of vividly identified, powerfully structured, highly useful mental images of the environment." (3).

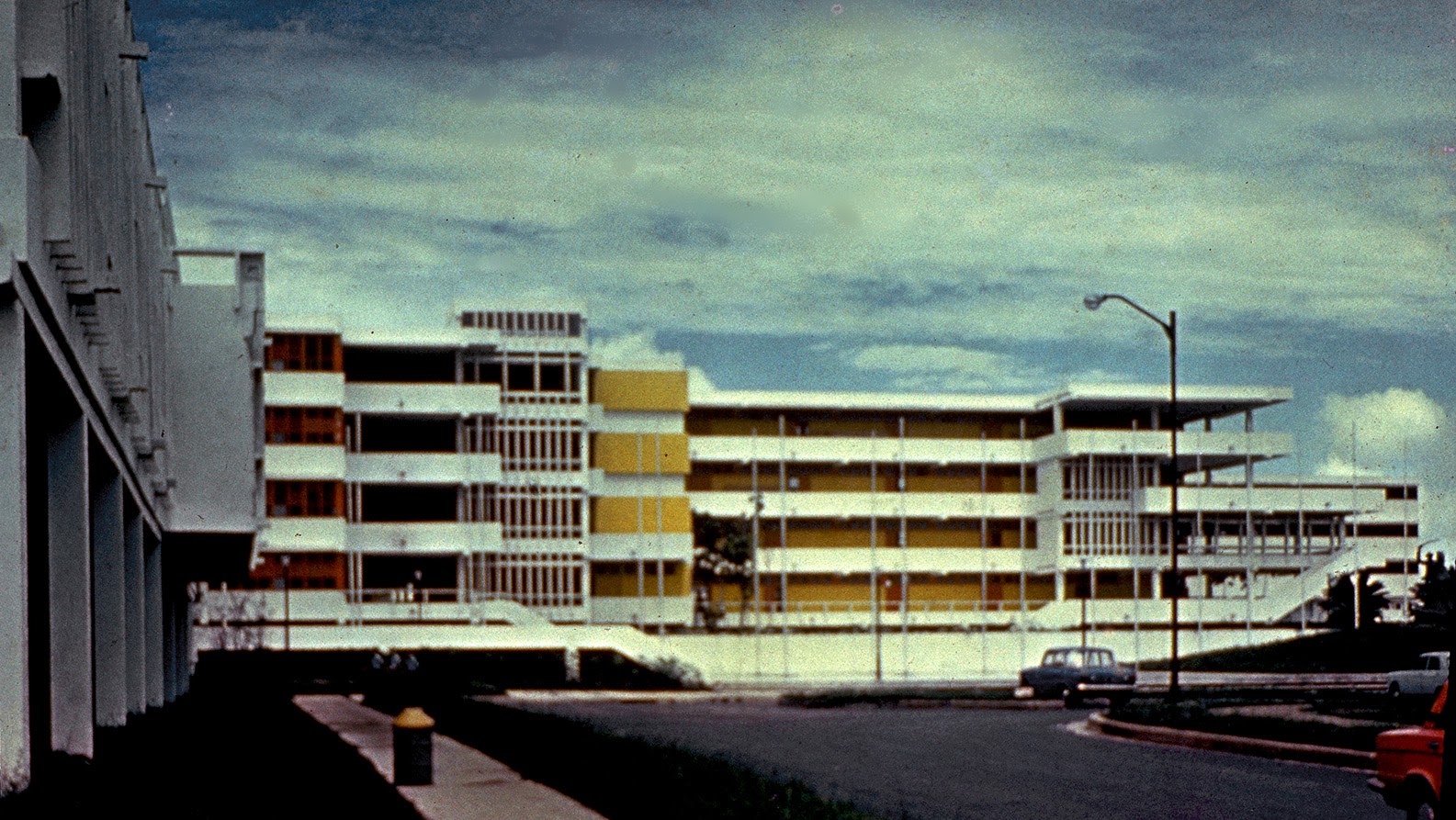

Being active as an Architect and a Teacher at the same time made possible both testing classroom theories in real practice and proposing tasks related to my ongoing projects in class, an enrichening experience for all of us. What I tried to attain in my design for the Camagüey Vocational School (4) was to break with the horizontality, the parallel alignment of buildings, the blind building endings and the lack of visual connection to the terrain. The east-west alignment of classroom blocks and bedrooms was conditioned largely by climatic conditions, particularly sunlight. However, the common use premises such as library, museum, computer center, theater, etc., are grouped in a north-south orientated central block acting as a symmetry axis around which the whole is articulated. The project was organized around a central axis which grouped the common use facilities and two sectors on either side of this axis that would correspond to the two school levels -high school and senior high school- to which these facilities originally gave service (5). The bilateral symmetry is only approximate since it must accommodate to a number of factors, among them the construction sequence which provided for the phased implementation of the project, the need to include the cooking and dining facilities in the first stage, the presence of an outdoor amphitheater which was also intended for activities of the neighboring city but that should not interfere with teaching activities and finally, the difference in the number of students, higher in high school than in senior high school. In addition we felt that from a formal point of view an overly strict symmetry would reinforce the duality of the layout at the expense of its unitary perception. This unity is evident, from the inside, in the articulation of squares and other areas between buildings which assume diverse functions depending on the characteristics of their surroundings. From the outside this unitary character is strengthened by emphasizing the central core through the concentration of built volumes, the greater complexity of its geometry and its careful characterization. The focus on science expresses itself in the location in the prominent position within this core of those facilities to them dedicated: the laboratories, the computer center, the library and the museum, built using the same prefab system but with an idiosyncrasy of its own incorporating certain constructive elements designed specifically for this project. Among them special attention is deserved by the guardrail panel system that characterizes the grid in which the buildings are inserted and establishes an autonomous plane of interconnection not dependent on the site's topography. While the depth of class and bedroom blocks is preset to meet standard distributions, mounting flexibility with cranes on wheels is used to achieve far more complex spaces in the other buildings. Some things were inherent to the construction system and could not be changed. For example the limitation on height, no more than four stories. The personality of this school lies largely on having achieved to visually overcome this limitation. For this purpose two staggered plan towers that house rooms intended for laboratories were placed at the ends of the classroom blocks bordering the central block. To emphasize these towers we added projecting volumes (used for storage) that were painted bright yellow color. A sudden change in height takes place beside these towers, to the library's two stories (the lower one resting directly on the ground), thus emphasizing by contrast the impression of height. Viewed from the main entrance a perspective effect takes place due to which the buildings -the dormitories- farthest away in the background look smaller, then the approaching classroom buildings and lastly, closer by, the laboratory towers on either side of the central block, lower in height as I said before and linked to the ground by the colonnade on which the library is supported. The central core includes the school's main entrance. It not located facing the access road, instead it is oriented sideways, conforming a ceremonial space which culminates in the equestrian statue of the Generalissimo by the sculptor Delarra. This space is a square and at the same time an entrance, reinforcing with this ambivalence, inner space / outer space, the sense of a relatively closed autonomous community. Another aspect in which we resort to a kind of optical illusion is in solving the dormitories' blind endings. At the ends of the classroom blocks I had placed the main staircases, thereby justifying these opening them with terraces. But I could not do this in the dormitories since these were typical projects, drawn up by architect Andrés Garrudo (6). | The solution was to paint these façades so that the play of light and dark colors -suggesting effects of light and shadow- as well as the use of warm colors (that "advance" visually) and cool colors (which "recede") would give the impression of the relief that these walls lack. The red and violet on the balconies -protruding both as perceptual code and physical reality- are continued on the building extremes' facings, as do the blue and green from the windows -back physically and as perceptual code- giving rise to a dual reading -physical plane vs. coloristic code- in which the suggestion of relief prevails. | ||||||||||||||||||||||